It’s Wednesday afternoon and my fifth-grader is sitting at the dining room table hunched over my husband’s laptop. I assume homework is taking place, but when I ask what he’s working on, Everett tells me he’s reading a story he wrote in the third grade.

Flashing me a smile, he says, “I can’t believe I wrote this.”

I immediately interpret his words to be self-deprecating. As in, Wow, I’ve come a long way, or Wow, this is embarrassing.

But later at dinner during a game of High Low Buffalo—where we recap the best and worst and silliest parts of our day—Everett says, “My high is that I read a bunch of stories I wrote in third grade … and I couldn’t believe how good they were.”

I study his face, full of sincerity, as I realize what he actually meant earlier.

How does he do it? How does my ten-year-old son look back on his writing from two whole years ago with a sense of genuine adoration? Whenever I read something I wrote even two weeks ago, I cannot help but hold it under a microscope looking for errors. All I see is room for improvement: every line that could be better, each word choice that could be stronger, piles upon piles of missed opportunities.

As for stories I wrote two years ago? I can hardly stand to look at them.

Which is a real shame and cause for concern, because a lot of those stories have been printed in a book. Copies are being shipped to doorsteps as I type this.

///

I’m sitting in a wooden folding chair at a writer’s conference in Marin, California. The first speaker to take the stage is explaining the difference between “average” perfectionism and “severe” perfectionism. Before she even offers a distinction between the two, I know which type I suffer from.

She asks everyone to journal for five minutes about what perfectionism feels like. I grab my pen and notebook and start writing on a blank page.

Perfectionism feels like hands on my throat. Like I can’t breathe. Like I’ll never measure up, and never be good enough. It feels like a brick wall I can’t get through. No matter what, no matter how hard I try, the stories in my head will never translate on paper as beautifully as they appear in my head. It feels like climbing uphill in quicksand. Like the harder I try to rise, the more I sink. It feels like failure. Embarrassment. Desperation. Exhaustion.

I’m still writing when the speaker’s voice echoes through the microphone, snapping me back to reality.

“Severe perfectionism,” she says, “is often a struggle that stems directly from childhood wounds.”

She pauses, softens her stance against the podium. The room falls silent.

“Therefore, severe perfectionism is not a problem to fix, but something that needs to be healed.”

///

Standing in the kitchen, I carefully slice open a cardboard box with a pair of scissors, holding my breath. My husband appears beside me as I comb through dozens of packing peanuts to reveal what I already know is inside: three copies of my book.

I pull one out gently and examine each side, the way I’d study a pear in the grocery store before placing it in the cart.

My husband says, “Wow.”

I say it back. Wow.

He grabs a copy from the box and heads to the couch, where he immediately cracks open the spine and begins to read.

I take the other two books and carefully place them on a shelf out of reach from sticky hands.

I am too scared to look inside.

///

One day my husband and I are cleaning the garage when I come across a plastic bin of childhood items my mom saved for me, old artwork and school projects. I can’t help but notice the number of certificates and awards: outstanding achievement in multiplication facts, second place in a creative writing festival, an “Eagles of Excellence” award for “being very helpful to others and an excellent worker.”

At the bottom of the bin, I spy the gold ribbon for the Young Authors Contest I won in third grade, paired with the story I wrote: Mom, I’m Growing Up.

The book is written and illustrated on white printer paper, hole punched and threaded with hot pink yarn through what appears to be two flat pieces of cardboard wrapped in decorative wrapping paper. I have no memory of making this, but if I had to guess—the other kids likely turned in their stories held together with a simple staple.

The date on the front page reads March 14, 1995—a little over 28 years ago. I crack it open and begin to read, amused.

The opening scene features a girl named Ashlee who is trying on a pair of “babyish” overalls her mom had picked up for her at the mall. Right away we learn Ashlee’s mom, Elizabeth, is overbearing.

This line catches my eye in a haunting sort of way: Ashlee always felt as if she never did anything right.

Elizabeth insists Ashlee wear the overalls to school the following morning, which completely destroys her reputation. Her own best friend ignores her, unable to forgive such a fashion faux pas. The next few pages detail Elizabeth treating Ashlee like a baby, horrifying and embarrassing her at every turn.

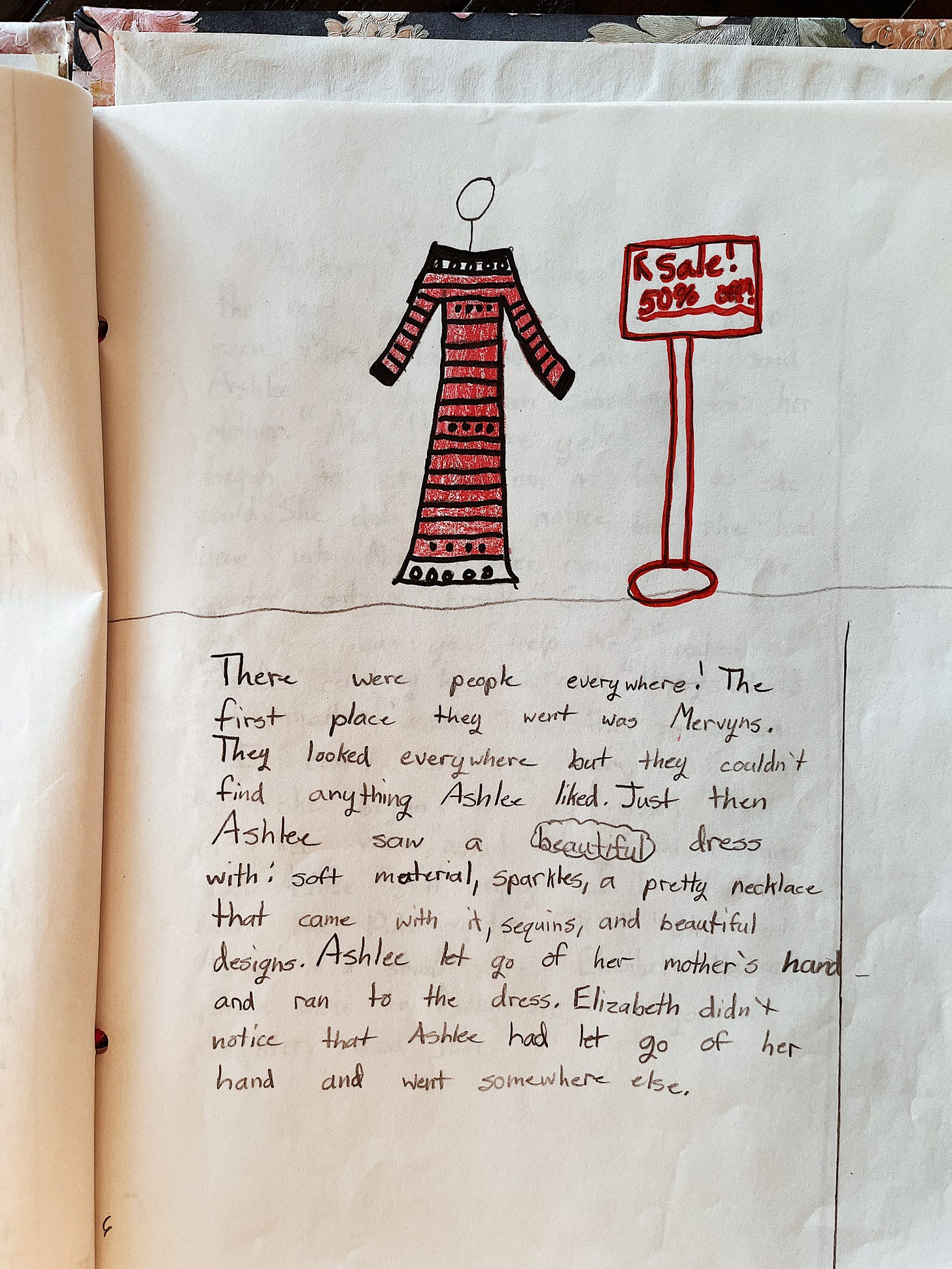

Finally, a chance for redemption: it’s Ashlee’s birthday. She’s another year older and wiser; surely her mom will stop this nonsense! They venture to the mall to buy a birthday present, where they land at Mervyns, a popular department store.

When Ashlee stops to admire a beautiful sparkly dress, she lets go of her mom’s hand and the two get separated. Panic ensues. Ashlee runs to a saleswoman out of breath, who offers to call Ashlee’s mom over the PA system. When the PA call doesn’t work, Ashlee suggests Julie page her mom on her beeper. Elizabeth feels the pager vibrate, calls the number, and the mother and daughter are reunited at last.

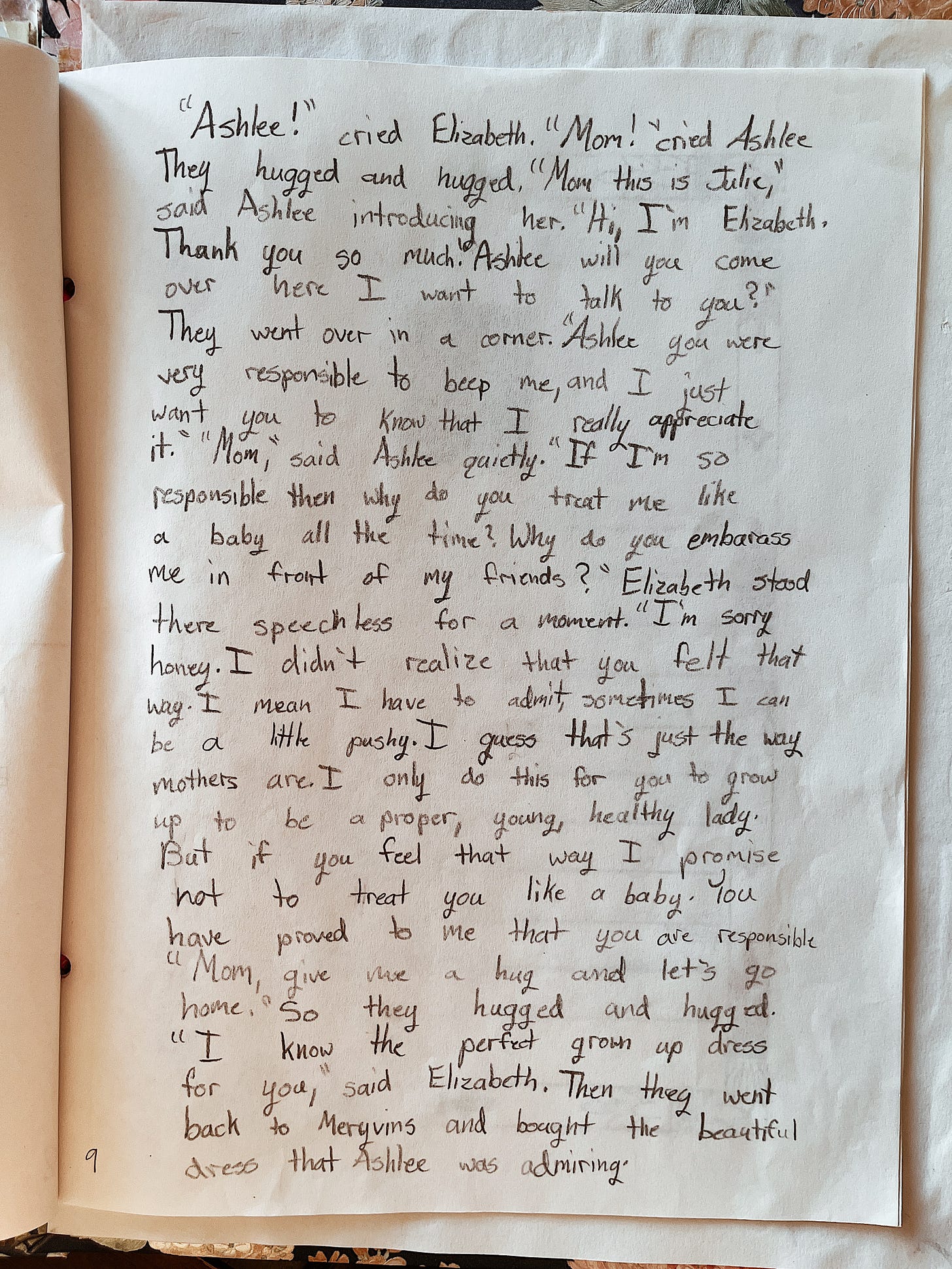

Elizabeth, grateful and relieved, tells Ashlee how responsible she was to find an adult and page her beeper. And then Ashlee says quietly, “Mom, if I’m so responsible, then why do you treat me like a baby all the time?”

Elizabeth is speechless, but finally apologizes and promises to stop treating Ashlee like a baby. The story ends with Ashlee and Elizabeth hugging each other, and then going back to Mervyn’s to buy the original dress Ashlee had been admiring.

Dare I say it: the story is good. Really good. The plot, the narrative arc, the setting and word choices and dialogue—I can practically see the Judy Blume influence jumping off the page. At nine years old, I was already taking my real life emotions and processing them through stories.

I close the book with a smile on my face.

I can’t believe I wrote this.

///

Another speaker takes the stage and boldly declares, “Most writers don’t have a problem with discipline; they have a problem with devotion. You can’t love your writing if you constantly hate it.”

That line swirls in my head for weeks after I leave the conference.

You can’t love your writing if you constantly hate it.

You can’t love your writing if you constantly hate it.

You can’t love your writing if you constantly hate it.

///

I’m combing through my inbox when I get two identical notifications from each of the boys’ teachers. The school talent show is happening in a few weeks. Anyone who wishes to participate must fill out a form in advance and attend the upcoming mandatory rehearsal.

After skimming the email, I call over to Everett who is reading on the couch.

“Ev, do you want to be in the talent show?” I ask, suggesting he play a song on the piano.

He briefly looks up from his book and considers the question for a few seconds.

“What if I mess up?” he asks. “How many people will be there?”

I open my mouth to give him a pep talk but hypocrisy catches in my throat. What he’s really asking is: if I fail, how many people will see it happen? A question I’ve asked myself no less than 100 times. A question that has stopped me, paralyzed me, and choked me up more often than I’d like to admit.

Before I utter a word, he says, “Do I have to?”

I take a big breath. As much as I’d love to force him out of his comfort zone, call this an opportunity for courage, a chance to practice “a growth mindset” as they say at school, I know Everett has to make this choice for himself.

He can get on the stage and share his talent with the world, or watch silently from the audience.

One comes with risk of failure; the other comes with risk of regret.

///

Notebooks and styrofoam cups of lukewarm coffee are scattered around us as we collectively complete the next exercise. Together we make a list of writer attributes, shouting out words across the table.

What is a writer?

“Brave!”

“Honest.”

“Curious.”

“Hopeful.”

“Vulnerable.”

What do writers need to have?

“Courage.”

“Devotion.”

“Imagination.”

In tiny letters, I add a word to the bottom of my list.

self-compassion

///

It pains me to admit this: my book is not even sitting on shelves yet, and I am already grieving the loss of its full potential. I’ve got something like 50 copies of Create Anyway in my possession at this point, and I still haven’t been able to bring myself to read it.

If I were speaking to a friend, here’s where I’d get quiet and gentle. Honey, you’re crazy. Stop speaking death over this book before it even has a chance to live.

I am trying to speak to myself with compassion. I am trying to go back to the roots, to the problem that needs to be healed. Me, a little girl, translating “I’m so proud of you” into “I love you.” Me, a teenager, earning good grades and racking up accomplishments while all the grown-ups beam at how responsible and smart and hard-working I’ve become. Me, twenty-three, desperately trying to find my place in this world, climbing the ladders, starving for validation, swallowing every opportunity like a magic pill—waiting to be changed, waiting for that tiny hole in my heart to finally be filled.

Sometimes I wish I could cup my childhood face in my hands, burn the report cards, throw out the trophies, stuff every award into a bottle and toss the whole thing out to sea.

You are loved.

You are loved.

You are loved.

For now, I simply pray that one day—whether it’s a year from now, or 15 years from now, or 30 years from now—I will be able to read Create Anyway cover to cover with a genuine smile on my face and say, “I can’t believe I wrote this.”

Create Anyway releases tomorrow (!). Today is the last day to pre-order, which is the best way to support me, and support this book. You may not know this, but Pre-orders matter. A lot.

Pre-order here and get instant access to the Mother Artist Diaries, a candid video series I made with my friends. ❤️

Easy links: Target | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Bookshop | Baker Book House | Christianbook

P.s. Early reviews are in via Goodreads if you want to see what other women are saying about the book. (Thank you, launch team! 😭)

Finally pre ordered. Thanks for the nudge. I picture Presley reading this when she is a mom. When she is doubting herself. And thinking...”wow, my mom was so brave.”

Oh my gosh, the side by side "About the Author" pictures make me teary, friend! I love every word here, every word you've ever written. I can't wait to see what God keeps doing here.